Over at Betsy Lerner’s blog, she posted William Carlos Williams’ iconic poem, raising the question of what a reader brings to a work, how the mind takes the words and converts them back into experience, and how uniquely each individual does that. I took up the question of “how many chickens,” turning it into a very involved joke, but by the end it turned into something else.

Over at Betsy Lerner’s blog, she posted William Carlos Williams’ iconic poem, raising the question of what a reader brings to a work, how the mind takes the words and converts them back into experience, and how uniquely each individual does that. I took up the question of “how many chickens,” turning it into a very involved joke, but by the end it turned into something else.

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

“XXII” —William Carlos Williams

It’s all about the chickens. For this reader, the wheelbarrow serves as a kind of subterfuge, a poetic shell game. Like a magician, Williams misdirects our attention with the red of that simple machine, its glittering glaze of rainwater, then conjures up a flash of white wings and tail-feathers at the end, just as any good prestidigitator generates doves from his cape.

So much depends upon this wheelbarrow, true: not merely for what it carries or holds, but for the entire trajectory of the poem, culminating in the Zen-like denouement of the chickens. Of course, the barrow may be empty; Williams doesn’t say. More Zen-ness. Why did Williams write this poem, this way? Who knows? But this mere slip of a verse, one whose influence has grown out of all proportion to its length or subject matter, a few lines that have exercised students’ and writers’ wits for well-nigh a century, is become a genuine made-in-America koan.

But why couldn’t Williams simply have written about chickens and have done with it? Why drag (roll?) the wheelbarrow into it? Well, for one thing, a poem solely about chickens would likely, unfortunately, be taken for a joke, what with their clucking and strutting and indiscriminate defecating. Chickens, as poetic imagery, are cursed to be perpetually humorous, whether we (or they) like it or not.

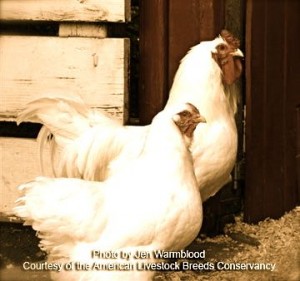

And yet—so much depends upon them! And since this is meant to be a serious poem, the weighty wheelbarrow imagery lends dignity and gravitas to the fowl [I count two—at most, four—Rhode Island Whites]. Chickens usually run in larger flocks, but that would scatter the energy of the poem’s spare imagery too widely: two is the smallest number you can use—a single rooster might be taken for a pet—and still preserve the focus and “loneliness” of the wheelbarrow, and of the poem as a whole.

One could argue that chickens and wheelbarrows are of equal necessity on a family farm, and undoubtedly in ordinary times this is so. But when things get bad (as they are sure to, eventually), the chickens’ preeminence invariably comes to the fore. Of course, there are those who insist upon the equality and even the superiority of the wheelbarrow: “Give a man a chicken and he eats for a day, etc.” But the wheelbarrow’s ostensibly central role in this poem is due to its actual position as a “set-up” for the chickens, as will be demonstrated.

“The Red Wheelbarrow” [ its common name; scholars despise this appellation. The poem is properly known as XXII], is a uniquely and iconically American poem, what with its eschewing of traditional British stressing and its Steiglitz-influenced imagery, but universal in appeal, crossing at least one cultural border. Indeed, it has been compared in its minimalist construction to the haiku of the great Basho. This is an astute reading, being that the ending of a haiku is somewhat analogous to the “punch-line” integral to American jokes. And what better punch-line for an “American haiku,” both in terms of sense and of sound, than “chickens”? Try as we may, the word’s intrinsic barnyard jocundity cannot be repressed. A stroke of subtle comic genius on Williams’ part, it must be agreed.

Still, the question remains: what, or who, depends upon the wheelbarrow? The chickens? It is not a farfetched proposition, since there may be something in the wheelbarrow that they like to eat. Some unknown farmer facing a locust-plagued field near harvest time? The possibilities for evoking dramatic tension and poetic transcendence are limitless. But we need not subject more generations of budding scholars to this migrainous enigma. One might put forth that the very survival of a farm, along with its generations of inhabitants, human and animal, depends on the presence and reliability of artifacts such as the humble wheelbarrow. But Williams conspicuously makes no mention of such, and besides, such a prosaic truth goes only so far. Just as we would not, without good reason, add an apple to a tree or, for that matter, insert an egg into a hen, we cannot search for answers to the poem’s meaning from without. Like the apple or the egg, its meaning is born of itself, not imposed by the reader. It is not by mere idle whim that, in its final lines, Williams emblazons on our mind’s eye neither stacks of firewood nor piles of stone (which have already been done to death by Frost), which would have been the more logical pairing with a wheelbarrow, but the image of cumulus-colored (not filthy, as some have speculated) fowl standing by in companionable intimacy, clucking softly. While seemingly incidental to the wheelbarrow, we might stake all on the possibility that their presence is actually the answer to the koan/riddle suggested by the words “so much depends.” The poem’s whole meaning—or at least so much of it—depends upon the solution to the mystery which arises from that phrase.

But perhaps the riddle is insoluble, the koan leading only to the void. Perhaps the question to be asked, rather, is this: upon what does the poem itself depend? For the fate and fame of Williams’ red wheelbarrow is indelibly graved in the halls of Literature only and forever by its ending. The final four words echo in our collective memory (Hardly anyone remembers the part about the rainwater) like a faint but insistent chord. And because it hides within its heart the soul of America, the poem must end in happiness, or at least hint at the promise of such.

I have to pause here. I’ve been working on this for most of the day, prompted and impelled at first by a kind of show-offy, nonsensical mood, later by the perennial human habit of seeking, then finding or making meaning in something whose meaning is not immediately clear, although I’ve never been in doubt as to what this poem is about. In making an extended joke about this poem (though I am partial to chickens), I now suddenly find myself serious. In trying to come up with my own punch line, I’ve painted myself into a corner. The poem, as it turns out, means more to me than I thought it did. Or did I make the meaning as a result of writing around it? The poem, on its surface, is about human hope and survival in the face of nature, the rain and the earth and its animals. Is it rash to not exactly anthropomorphize, but maybe humanize the players in this poem?

I think this poem has endured, not because of the enthusiasm of English teachers, but because it’s a parable. It points to a union upon which not just human survival but human culture depends. It points to a once-committed partnership, of ancient and fraught duration, one which most of the world now seeks to escape via constant technological escalation. It is a wedding portrait: the reliable and strong, silent and ruddy, but most of all, dependable red wheelbarrow standing beside the white-bedecked you-know-whats—a mutual domestication, with the heaven-sent rain blessing all.

{ 5 comments… read them below or add one }

How much do I love that this poem is what brought you out of obscurity? It’s perfectly sensible, in my estimation.

When I first read the poem at Betsy’s place I instantly saw the scene in my head. I don’t know if it was the words themselves that prompted me or whether I wanted to follow in Betsy’s footsteps but whatever the cause, I quickly had the image in mind. It was a pretty picture and I left it at that.

Reading your analysis, however, has opened my senses. For me, it becomes all about the wheelbarrow. “So much depends upon…” is the phrase that I keep coming back to. The chickens, of course, depend upon the wheelbarrow but what else is there? The farmer, the farmer’s family, the crops, the market where the crops will be shopped, the public that depend on those products, the other animals. The list feels endless.

And yet the wheelbarrow cannot function without a human hand. The sturdy, steadfast machine is dependent upon something, as well. It is here where mutual need is highlighted.

I just remembered that I have pictures of chickens I took two summers ago. I wonder if I caught a wheelbarrow in that lot. You’ve inspired me to go and take a look.

It started off as a little comment on Betsy’s blog: “It’s all about the chicken.” And then I couldn’t stop. I woke up feeling a little embarrassed this morning. I was trying to spoof the whole idea of analyzing the poem the way we try to in school by making it about the chickens, but then I couldn’t sustain the mood.

Are the chickens in your photo yours or just strangers? I’m strictly a lacto-vegetarian (no eggs), but I enjoy the company of chickens. Watching them is better than TV.

It is amazing how much can be said about one little poem. I often wonder whether authors like this are even conscious of what they put forth or if they’re even sober when they produce it.

I went back but didn’t find any wheelbarrows. Lot of chickens and cows and even a few buckets but no wheelbarrows. I wish they belonged to us. We considered getting some but realized our persnickety suburban neighbors wouldn’t take too kindly to the early wake up calls.

Tulasi-Priya, as I live and breathe. Blogging! My world is almost complete.

My sister has chickens, and I agree they’re completely adorable. So much personality from their tiny little bird brains.

You drew me far into this little web and I had to stop and try to figure out for myself what this poem meant in my mind.

I enjoyed the dizzying twists and turns you took throughout this, but your interpretation at the end thrills me. For myself (and I admit I’m unable to separate what I might have meant from what Williams may have meant) I see a painting or a photograph with the decision to capture that red wheelbarrow gleaming with water as the thing that sets the image apart and etches a patch of yard with chickens into memory.

{ 1 trackback }